- 1. Why is agentic AI governance so important today?

- 2. What are the main risks of AI agents?

- 3. Who is responsible when AI agents act autonomously?

- 4. How to implement agentic AI governance

- 5. Where governance applies in the AI agent lifecycle

- 6. How standards and regulations influence agentic AI governance

A Complete Guide to Agentic AI Governance

p>Agentic AI governance is the structured management of delegated authority in autonomous AI systems that plan and execute actions on behalf of an organization.

It sets clear boundaries on what agents can access and perform at runtime. Governance extends beyond model alignment, compliance, or monitoring by establishing explicit oversight and accountability for agent behavior.

Why is agentic AI governance so important today?

Agentic AI represents a structural shift in how organizations use artificial intelligence.

Earlier systems primarily generated insights. Human operators decided what to do next. Today, agents increasingly execute tasks directly within business workflows.

Enterprise adoption reflects that shift. Agentic AI could unlock $2.6 trillion to $4.4 trillion annually across generative AI use cases, according to McKinsey & Company, Seizing the agentic AI advantage.

Yet only 1 percent of organizations consider their AI adoption mature, as reported by McKinsey & Company, Superagency in the workplace: Empowering people to unlock AI's full potential. Experimentation is accelerating. Governance maturity is not.

The difference is execution.

Agents can plan, call tools, and act across systems with limited supervision. They introduce new operational authority. And early deployments have already surfaced risky agent behaviors in production environments.

However, most AI governance programs were designed for model outputs, not autonomous actions. Oversight often stops at training validation or pilot controls.

The implication is clear.

As AI shifts from generating answers to initiating decisions, governance must evolve from policy alignment to sustained operational control.

How does agentic AI governance differ from traditional AI governance?

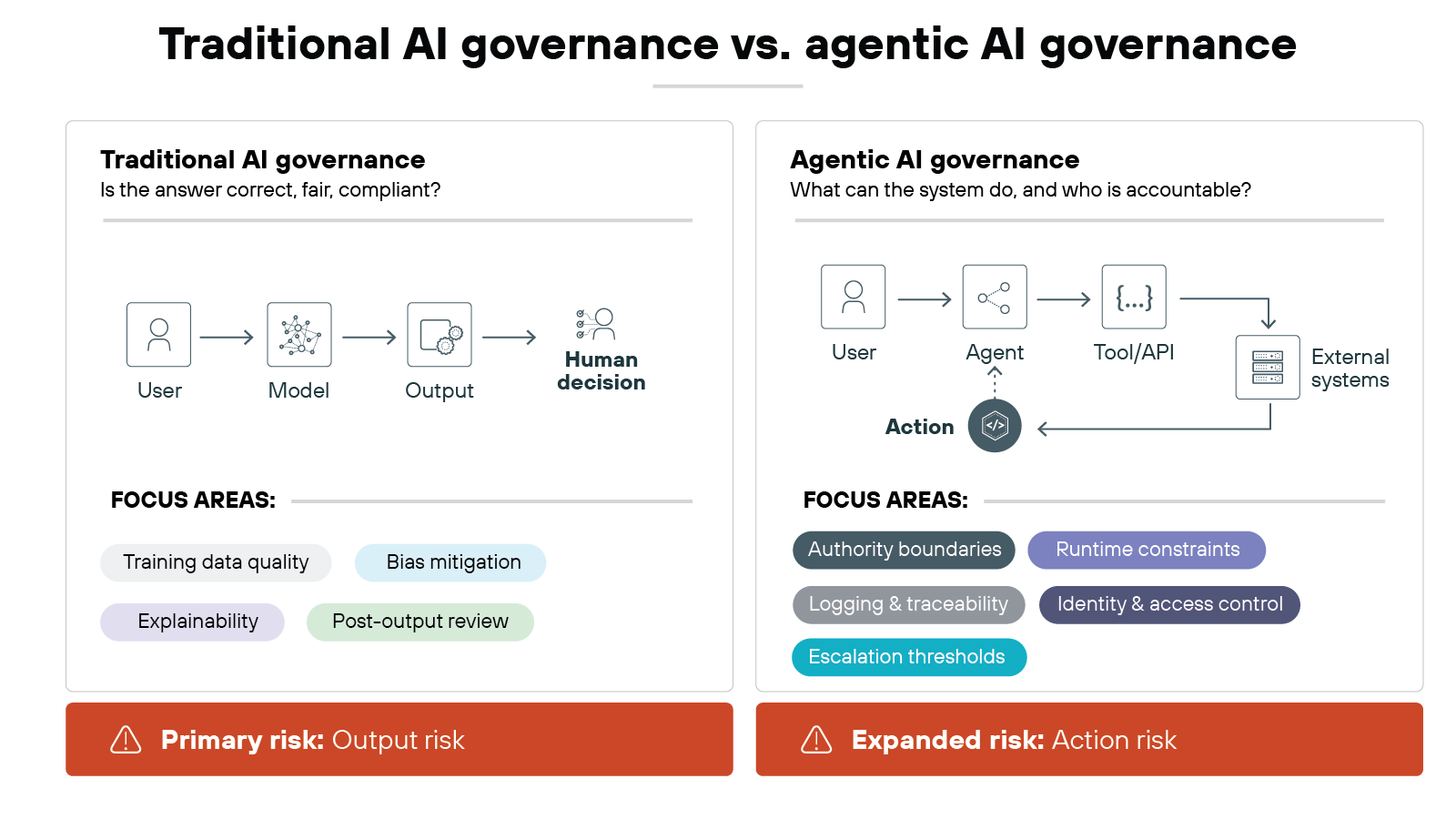

Traditional AI governance focuses on models that produce outputs.

Systems generate predictions, classifications, or text. Humans review the results and decide what action to take. Controls center on training data, bias mitigation, explainability, and post-output review.

Agentic systems introduce a different operating model.

Agents plan. They call tools. They execute multi-step workflows. They act within business processes rather than outside them. Decisions unfold over time instead of in a single response.

That distinction matters.

Traditional governance emphasizes output risk. The main concern is whether a response is accurate, fair, or compliant.

Agentic governance must also address action risk. An agent may initiate a transaction, update a record, or interact with another system without waiting for human confirmation.

Authority changes as well.

Agents can inherit credentials. They can access APIs and internal services. They can collaborate with other agents in coordinated workflows. These capabilities expand the scope of impact beyond a single model output.

Accountability becomes more complex. Responsibility may span model providers, platform operators, and deploying organizations. Which is why clear role definition becomes essential.

In practice:

Governance has to extend beyond model alignment into runtime action control.

What are the main risks of AI agents?

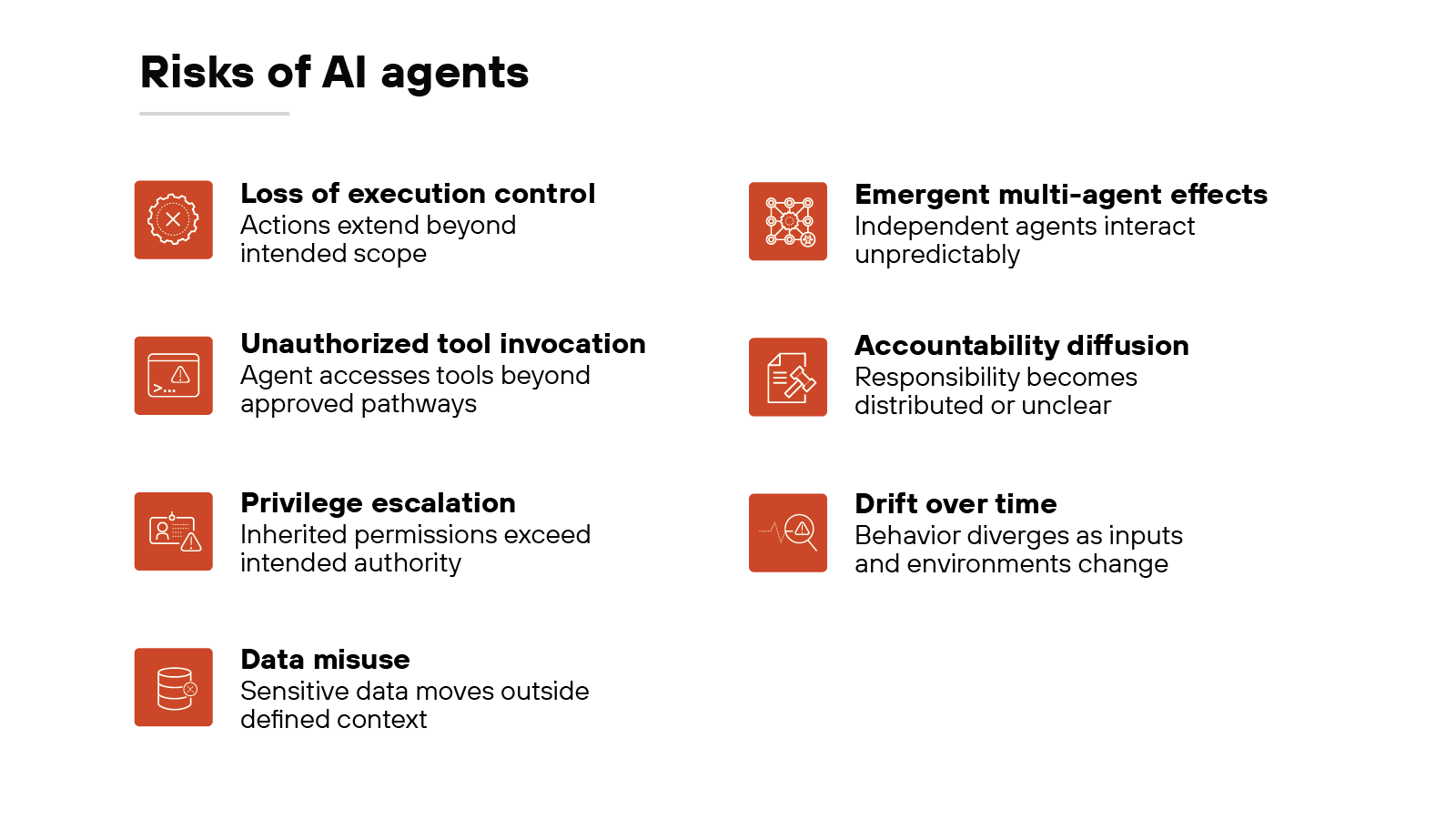

AI agents expand the scope of operational risk.

They don't only generate outputs. They execute actions inside live systems. As authority increases, so does impact.

However, not all risk looks the same.

Some risks involve execution boundaries. Others involve identity, data, or coordination between agents.

Governance requires understanding how these risk domains differ.

Let's break them down.

Loss of execution control

Agentic systems can initiate actions without direct human approval. They may continue multi-step workflows once a goal is defined.

If scope boundaries are unclear, execution can extend beyond intended limits. Control becomes harder to maintain when tasks chain together across systems.

Unauthorized tool invocation

Agents often integrate with APIs, databases, and enterprise services.

Improper configuration can allow access to tools beyond their intended scope. Even well-designed workflows can create unintended pathways when agents dynamically select tools at runtime.

Privilege escalation

Agents may inherit service credentials or operate under elevated permissions.

Misconfigured identity controls can grant broader authority than required. In multi-agent environments, trust relationships can allow one agent's access to influence another's scope.

Data misuse

Agentic systems process and exchange data across workflows.

Sensitive information can move between systems without clear visibility. Data can also be repurposed outside its original context.

Governance has to account for how data flows during execution, not just during training.

Emergent multi-agent effects

Multiple agents may operate within the same environment. Each follows its assigned objective. However, their actions can intersect in ways that weren't explicitly designed.

Small deviations can combine and produce broader operational consequences. System-level behavior may not always reflect the intent of any single agent.

Accountability diffusion

As mentioned earlier, responsibility often spans model providers, platform operators, and deploying organizations.

When agents act autonomously, decision authority can distribute across components. Without clear ownership definitions, accountability can become unclear.

Drift over time

Agentic systems do not remain static. Inputs change. Tools evolve. Business processes shift.

Over time, behavior can move away from its original design. What begins as controlled authority can gradually expand if not reviewed.

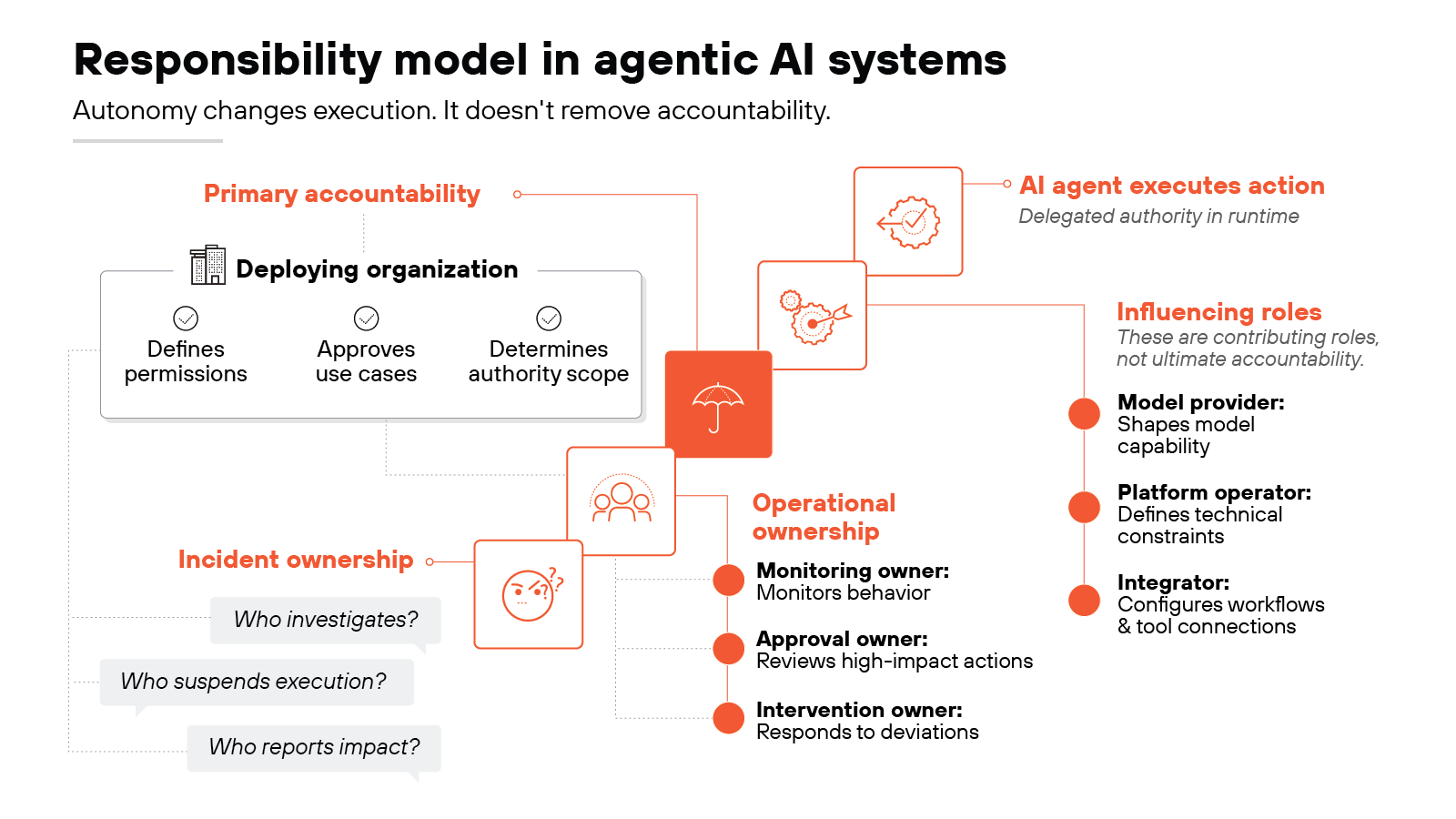

Who is responsible when AI agents act autonomously?

AI agents don't act independently of human authority. They act under delegated scope. Organizations define that scope.

However:

Delegation doesn't eliminate accountability.

Autonomous execution can create distance between action and decision maker. An agent may initiate tasks without immediate human review. But that doesn't transfer responsibility to the system itself.

Responsibility spans multiple roles:

Model providers shape system capability.

Platform operators define technical constraints.

Integrators configure workflows and tool connections.

The deploying organization retains primary responsibility:

It defines permissions.

It approves use cases.

It determines how much authority the agent receives.

Operational ownership has to be explicit, too. Governance should assign named individuals:

Someone who monitors behavior.

Someone who approves high-impact actions.

Someone who intervenes when outcomes deviate from intent.

Incident ownership also needs to be defined before deployment:

Who investigates unexpected behavior?

Who can suspend execution?

Who reports material impact?

Without clear answers, governance is incomplete.

Essentially, autonomy changes how systems operate. It doesn't change who's responsible.

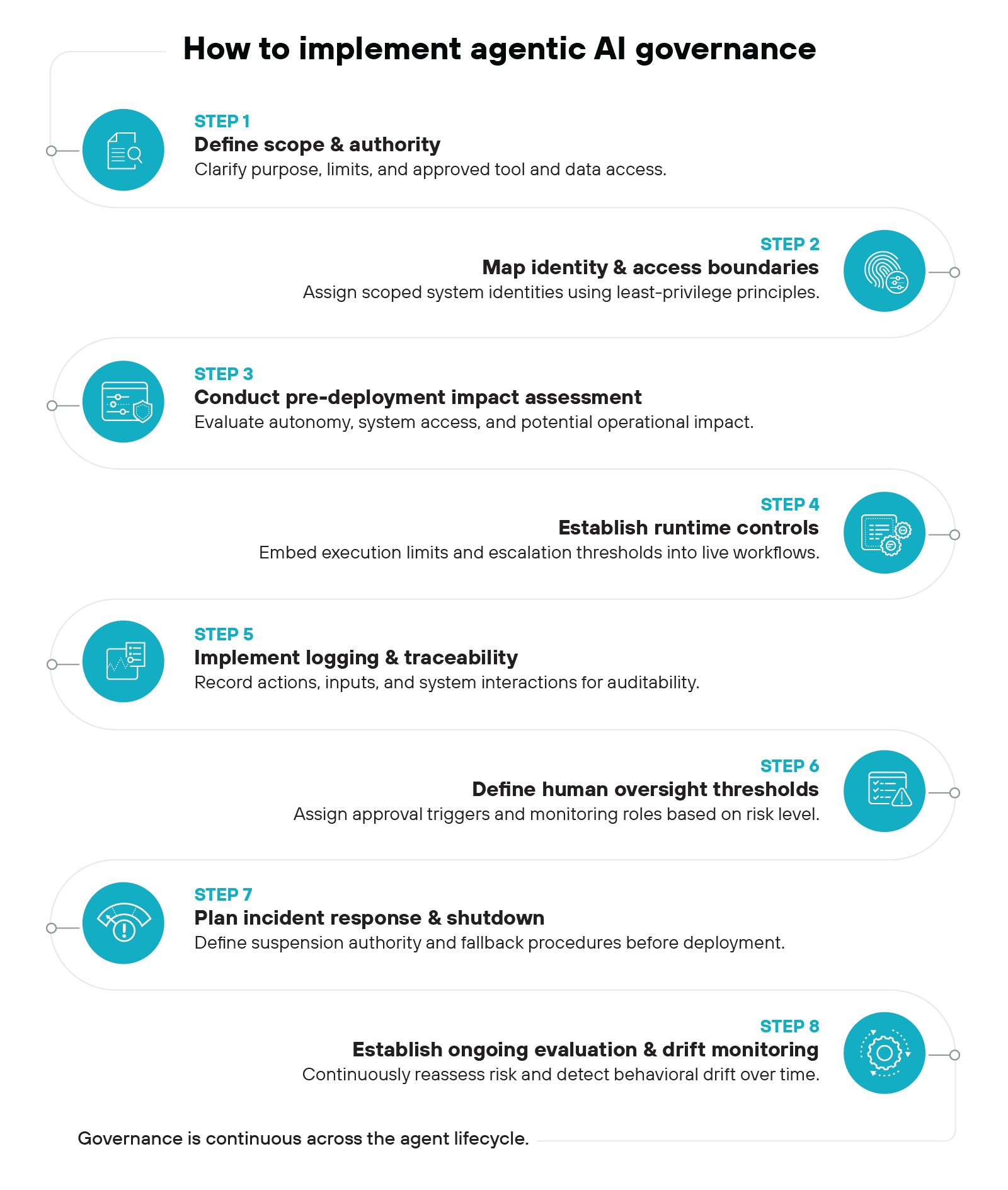

How to implement agentic AI governance

Governance becomes meaningful at implementation.

Policies and principles only matter when they shape how an agent is built, deployed, and supervised in practice.

That work follows a structured progression. It begins with defining authority and continues through runtime oversight and ongoing review.

Here's how that structure takes shape.

1. Define the agent's scope and authority

Governance begins with purpose. Every agent needs a clearly articulated objective and defined limits.

That scope should describe what the agent can do and what remains outside its authority. It should also define which tools and data sources are in bounds and which are not.

When authority is unclear at the start, controls become reactive later.

Tip: Document prohibited actions explicitly. Clear misuse boundaries reduce ambiguity and prevent silent scope expansion.

2. Map identity and access boundaries

Agents operate through system identities, not unlike human users. Those identities define what the agent can access and execute.

Permissions should follow least-privilege principles and reflect the agent's defined scope. Service credentials should grant only what is required for the task at hand.

Any inheritance of authority should be intentional and periodically reviewed to prevent silent expansion.

3. Conduct a pre-deployment impact assessment

Before activation, pause and evaluate impact. Consider how the agent's authority could affect financial, operational, legal, or reputational outcomes.

Autonomy level matters. So does the scope of system access. The more independent the execution path, the more deliberate the review should be.

A documented impact assessment strengthens governance and provides a clear record of how risk was evaluated before deployment.

4. Establish runtime controls

Training-time alignment alone doesn't address execution risk. Agentic systems operate inside live environments where actions can affect real workflows.

Runtime controls define what the agent can actually do once it's active. These controls limit tool invocation, constrain execution paths, and trigger escalation when defined thresholds are reached.

Guardrails need to function while the agent is operating. Not just during development or testing.

5. Implement logging and traceability

Autonomous execution requires visibility into what the agent is doing.

Actions should be logged. Inputs should be recorded. System interactions should remain traceable over time.

That traceability supports audit, investigation, and ongoing improvement. Without it, accountability becomes difficult to demonstrate or enforce.

6. Define human oversight thresholds

Not every action requires human approval. Some decisions can proceed autonomously within defined limits. Others carry higher impact and warrant direct review.

Governance should clarify when human-in-the-loop approval applies and when human-on-the-loop monitoring is sufficient.

Oversight roles should be assigned clearly so intervention is deliberate rather than reactive. The level of oversight should align with the authority granted to the agent.

7. Plan incident response and shutdown mechanisms

Agents do not always behave as intended. Environments evolve. Dependencies change.

Governance should clarify who has authority to suspend execution and under what circumstances. Clear fallback procedures should exist before activation, not after an issue emerges.

Isolation and shutdown capabilities should be validated in advance so intervention is controlled and timely.

8. Establish ongoing evaluation and drift monitoring

Governance doesn't end at deployment.

Agents operate in changing environments. Data evolves. Workflows expand.

Performance should be monitored against defined objectives over time. Risk should be reassessed as scope and context shift. Behavioral drift needs to be detected early so authority can be adjusted deliberately.

Ongoing evaluation helps maintain alignment as systems mature.

In practice:

Agentic AI governance brings together defined authority, disciplined identity controls, runtime safeguards, and sustained oversight. It reflects operational control in motion, not documentation stored on paper.

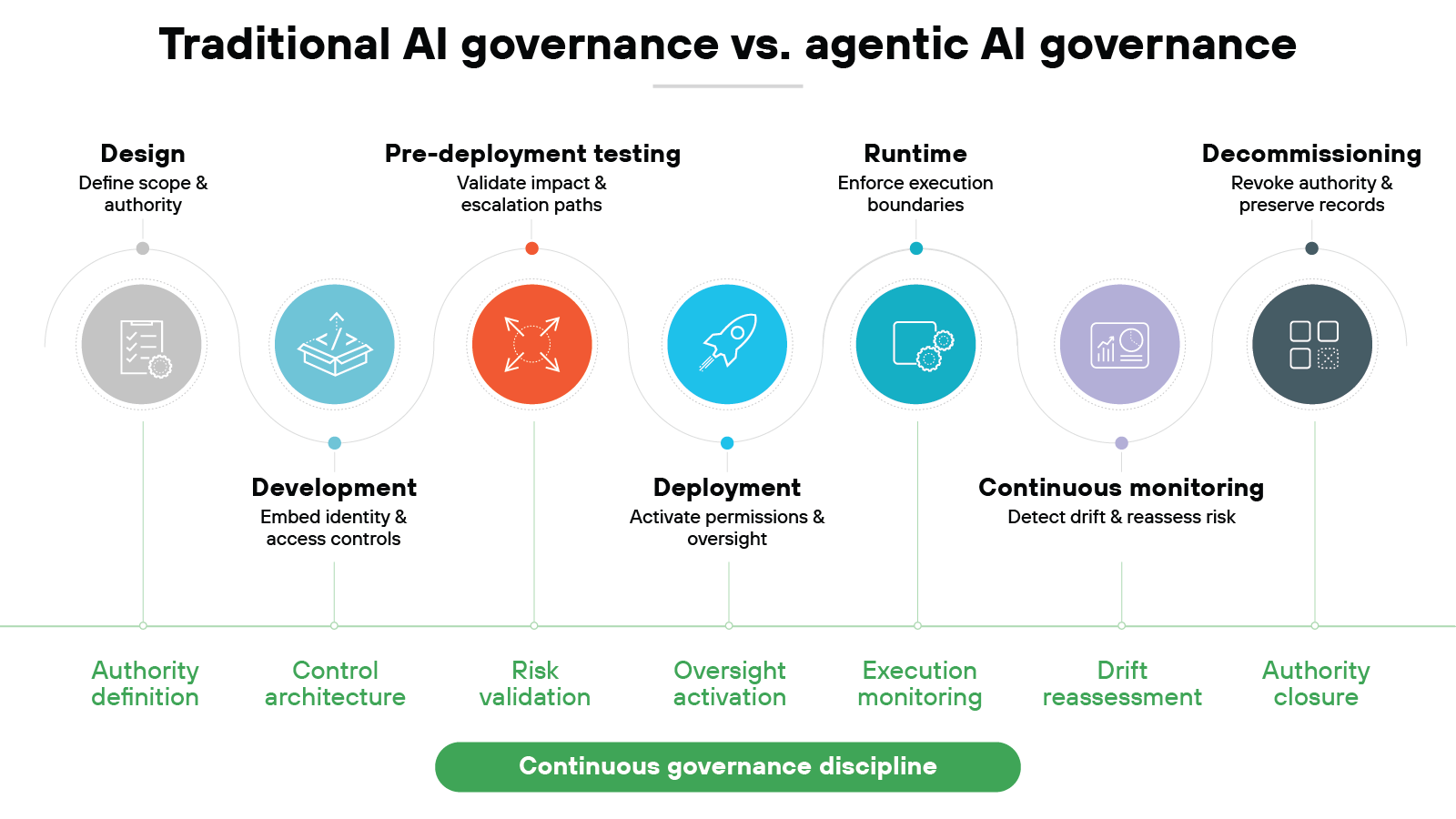

Where governance applies in the AI agent lifecycle

AI agents move through a defined lifecycle.

Governance has to move with them. It doesn't begin at deployment and it doesn't end at runtime. The focus shifts as the system progresses from intent to execution to retirement.

Governance appears at different points in that progression. Its form changes as the agent moves through each stage.

Design

Governance begins when the agent's purpose is defined.

At this stage, teams determine what the agent is allowed to do and what remains out of scope. Risk tolerance, autonomy level, and system access are shaped here. The intensity of governance later in the lifecycle often reflects these early choices.

Higher autonomy or broader access typically calls for stronger controls downstream. If authority boundaries are unclear at design, later controls tend to become reactive rather than preventative.

Development

During development, governance becomes technical.

Identity models are implemented. Access rules are encoded. Tool integrations are constrained.

Architectural decisions influence whether enforcement is feasible at runtime. Governance at this stage focuses on building controllability into the system itself.

Pre-deployment testing

Before activation, governance validates assumptions.

Teams test escalation thresholds, permission boundaries, and execution paths. Impact assessment moves from theory to simulation.

This stage confirms that authority limits behave as expected under realistic conditions.

Deployment

Deployment transitions governance from preparation to live operation.

Defined permissions become active. Logging and monitoring responsibilities take effect.

Oversight roles should be clearly assigned before the agent operates in production environments.

Runtime

Once operational, governance enforces discipline in real time.

Execution controls restrict unintended tool usage. Intervention thresholds guide when humans must step in.

Authority has to stay visible and reviewable while actions unfold across systems.

Continuous monitoring

Over time, systems evolve. Data inputs change. Workflows expand.

Governance reassesses risk as context shifts. Drift detection and periodic review help prevent gradual expansion of authority beyond original intent.

Decommissioning

Retirement is part of governance.

Access credentials must be revoked. Tool integrations must be disabled. Historical records must be preserved for audit and review.

Authority should end as intentionally as it began.

The takeaway:

Agentic AI governance is continuous. It adapts as the agent moves from design through decommissioning. Control is not a phase. It's a lifecycle commitment.

Example: Governing an enterprise AI agent in practice

Governance becomes clearer when applied to a real system.

Consider how it appears in a common enterprise use case:

-

Imagine an organization deploying an AI procurement agent inside its ERP system.

The goal is simple. The agent reviews routine purchase requests and creates purchase orders for approved vendors within predefined budget limits.

-

The authority is delegated.

A human owner defines what the agent may approve and what requires escalation. The agent can't change budget rules. It can't add new vendors. It operates only within its assigned scope.

-

That scope is enforced through identity controls.

The agent uses a service identity with limited permissions. It can access procurement records. It can create purchase orders. It can't modify financial controls or override approval hierarchies.

-

Every action is logged.

Each tool call and data access event is recorded. If a purchase order is created, the transaction is traceable to the agent's identity and timestamp.

-

Human checkpoints remain in place.

Transactions above a defined threshold pause for managerial review. Anomalies trigger escalation rather than automatic execution.

-

Governance also continues over time.

Spending patterns are monitored. Vendor selections are reviewed. If behavior begins to diverge from expected norms, permissions can be adjusted or execution suspended.

In short:

The agent executes tasks. Humans define the limits. Governance ensures authority remains bounded at every step.

How standards and regulations influence agentic AI governance

Agentic AI governance doesn't emerge from scratch. It aligns with existing risk and management frameworks that already shape how organizations govern complex systems.

Autonomous agents increase the urgency of applying those structures consistently.

Several established standards and regulations are especially relevant:

| Comparison of AI governance frameworks relevant to agentic systems |

|---|

| Framework / Regulation | Primary focus | Relevance to agentic AI governance |

|---|---|---|

| NIST AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF) | Risk identification and lifecycle management | Supports structured evaluation of autonomy, runtime risk, and continuous monitoring across Govern, Map, Measure, and Manage functions. |

| ISO/IEC 42001:2023 | AI management systems | Formalizes governance roles, documentation requirements, and oversight mechanisms within organizational structures. |

| ISO/IEC 42005 | AI system impact assessment | Guides structured pre-deployment evaluation of potential harms and operational impacts for specific AI use cases. |

| ISO/IEC 23894 | AI risk management alignment | Integrates AI risk into broader enterprise risk management practices and control models. |

| EU AI Act | Binding legal obligations for AI systems | Establishes requirements for risk classification, human oversight, documentation, and accountability for high-risk deployments. |

- AI Risk Management Frameworks: Everything You Need to Know

- NIST AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF)

- A Guide to AI TRiSM: Trust, Risk, and Security Management